Some Ideas About Things

Preface

Here I have written some ideas about things. The discourse is Cartesian in nature, starting from the assumption one knows nothing and seeing what can be discovered from direct sensory experience and reasoning. Be warned this is no philosophical treatise, but merely a first draft at summarizing some interesting discussions I’ve had with various University friends of mine. I should also mention that I am by no means an authority on philosophy. My only credential to be talking about things is the fact that I have experienced them for as long as I can remember. My only license to contemplate existence is the fact that I exist, and I perceive things that exist. And I invite you, having the same license and credentials, to deliberate as earnestly and openly as I have.

Does anything exist?

Consider the laptop (or tablet, phone, etc.) in front of you. You can see it. You can feel it. You can type on it. You can use it to make calculations, browse YouTube, and keep the time. And so on and so forth. Based on such observations, you conclude, it exists and is part of the ‘real world.’

But you can’t really know for sure. It is entirely possible that you are just a brain in a vat, with scientists hovering over you working tirelessly to prod your neurons with electricity so as to convince you that the world you experience is real when it is actually just an illusion. Everything you experience would only exist in your head. And it is impossible to determine whether this is in fact the case. But past this cursory remark, questioning whether reality is an illusion offers little more fruit, for the following reason.

Even if you are a brain in a vat, the laptop still exists. It doesn’t exist physically, but it does exist as an idea in your head. And of course it still exists! If it did not, it would not be called a laptop. For that matter, it would not be called anything. You would not be able to see it. You would not be able to feel it. You would not be able to type on it. And you certainly would not be able to use it for anything. We would not be talking about it to begin with. Moreover, if it did not exist, the scientists could not have formatted it into a series of electrical pulses to give to your brain to manifest as the idea of it. None of these things would occur if there were no such thing as a laptop. But clearly, as you continue to read my writing on it, there is such a thing, and so it exists.

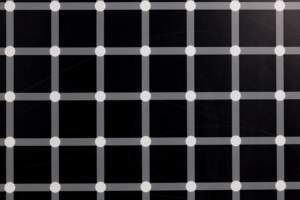

So the question is not whether things exist but whether they exist as they appear to. And to answer this you have no choice but to trust your senses, which you should do and must do, no matter how little you believe in reality. When your throat tells you that you’re thirsty, you drink. When your stomach tells you that you’re hungry, you eat. When your eyes tell you to duck for an incoming projectile, you duck. And so on and so forth. To be sure, your senses are not perfect—they fool you all the time. You see your friend walking, but when you look closer it is just a stranger. You hear someone call your name, but when you look around nobody is trying to get your attention. You fall victim to optical and audio illusions, such as the famous Hermann grid shown here. In such cases, you are perceiving things (such as the black dots in the image) that do not exist in the world as they appear to. Like the laptop in your head in a vat, they still exist, but they do not exist as they appear to.

While you can construct illusions and point out the failures of your senses, you have to cut them some slack! They are working tirelessly for you, and they are doing invaluable work. They are taking the external world, in all its wondrous complexity, disseminating the important details, and delivering it to your internal world. They are bound to make some mistakes, but they are doing the best they can, and for all intents and purposes, they do pretty well. Yes, they could be constantly lying, but it would be crazy to not trust them.

To conclude, some things exist, and you must trust your senses to tell you that they exist as they appear to.

Does everything exist?

Once it’s been established that some things exist, the next logical question is whether all things exist. I will attempt to tackle this by contradiction.

Let’s say we have a thing that does not exist. As it is now the topic of our inquiry, it ought to deserve a name. I will call it an “Arg.” Now this is what we have: an Arg is a thing that does not exist. And if it has a name and it remains the point of our discussion, we should recount its history. An Arg was first conceived by Cameron Witkowski on May 22nd, 2021 while he was writing some ideas about things. He named it after the original Arg—which was drawn by Cameron on May 20th. Both things named Arg were first used as discussion points in an argument, making their names fitting. Shortly after being conceived, our Arg—which does not exist—was outlined in words which were then typed into a computer. Some time later, you read these words, and the thing called an Arg entered into

your mind.

Herein lies the paradox. You could not see the laptop in front of you if there was no such thing as a laptop; and in exactly the same way, an Arg could not enter your mind if there was no such thing as an Arg. If an Arg did not exist, it could not have been put into words to be typed into a computer. It could not have been conceived, it could not have been named after the original, and it could not have a history. Most certainly, it could not be the thing you are currently thinking about.

One simple conclusion resolves this all. An Arg exists. More specifically, the thing that is called an Arg exists. The upshot of this all, as I’m sure you can guess, is that everything exists. Put another way, of all the things, each and every one of them exists. And an equivalent statement, by contraposition, is that no thing does not exist.

In the interest of simplicity and clarity, from here onward I will use the following litmus test for existence: if you can name it, it exists. The laptop in front of you exists because it’s called a laptop, and an Arg exists because it’s called an Arg. And so on and so forth. Why does this work? Because for it to be named requires it to be.

To conclude, everything exists because everything can be named.

Do unicorns exist?

“Unicorns are named unicorns, so are you trying to tell me that unicorns exist?” you comp

lain, “surely you must be mad.” Now here I must be careful with my words, so I ask, what exactly is the thing that you are calling a unicorn? Is it a living, breathing animal in a field that you are pointing to and saying “unicorn,” or is it an image of a horse-like creature with a single horn sticking out of its forehead, constructed entirely in your mind? Certainly, it is the latter, and that is the thing I’m talking about when I say “yes, unicorns exist.”

Now I must apologize for being so slippery and address what the question really asks: do unicorns exist in the flesh. “Haha! I’ve got you now,” you declare, “a unicorn in the flesh is just a thing that is named ‘unicorn in the flesh,’ but you cannot possibly claim that they exist too.” But here again I must ask: what exactly is the thing that you are calling a unicorn in the flesh? Is it an animal in a field that you are pointing to, or is it an idea in your head?

Now I am being slippery AND obtuse, so I will begin to wrap up my point. Certainly, without a doubt, if I went searching for a unicorn in the flesh I would not find one. But I could still go looking for it.

I could search the ends of the Earth. Whenever asked, I would say: “I am looking for a unicorn in the flesh.” I could look high and low, I could look near and far. I could form a search party with my University friends and we could look North and South, we could look East and West. And to anyone who asked, we would tell them: “We are looking for a unicorn in the flesh.” We could recruit more people until the search party was impressive. We could stage an effort so massive that it appeared on the news. And here is the point: if the broadcasters said in front of the world, “well, Cameron and his search party are certainly looking for something,” they would be absolutely correct. As before, to be searched for requires it to be.

Surely, unicorns are different from horses, pigs, cows, and the like. Horses, pigs, and cows came from their parents, who came from their parents, and so on, in a long chain of evolutionary history. Unicorns came from the imagination of some human beings from antiquity, appearing in ancient art, literature, and legend. Horses, pigs, and cows manifest primarily as complex multicellular organisms. Unicorns manifest primarily in drawings, fiction, movies and television. While horses, pigs, and cows also manifest in these mediums, unicorns do not manifest as complex multicellular organisms.

To conclude, yes, unicorns exist because they are named unicorns, and we would not be talking about them if there was no such thing.

Does external reality exist?

Yes, because it is named external reality, and again, all we can do is trust our senses not to lie to us that it exists the same way it appears to. However, there is nothing in reality.

Do words exist?

By all the previous logic, yes, because they are called words.